Projects

The cognitive regulation of internal states

Fear is an internal brain state underlying observable manifestations including defensive behavior and somatic responses (e.g., pupil dilation) (Review by Anderson & Adolphs, 2014). The neural mechanisms by which such internal states are generated and controlled are not well-understood. Fear is well-conserved across species and provides a tractable model for understanding how internal states are regulated. A circuit understanding of internal state control is relevant to the relationship between arousal and emotion, about which multiple competing theories exist; for instance, James-Lange theory proposes that bodily responses trigger emotions, implying that regulation of somatic response is critical for top-down control.

The psychotherapeutic treatment of psychiatric disorders strongly suggests that individuals can learn to exert cognitive control over internal states. The Stujenske Lab aims to explore how the medial prefrontal cortex mediates top-down regulation internal states via outputs to subcortical structures. In particular, the Stujenske Lab focuses on the cognitive regulation of fear by studying the process of discrimination between aversive and non-aversive stimuli.

Overgeneralization, in which negative affect states are triggered in both dangerous and safe situations, is a trans-diagnostic phenomenon affecting patients with anxiety disorders, OCD, and PTSD (Dymond et al., 2015), which are very prevalent but often refractory to treatment (Bystritsky, 2006). Striking a trade-off between discrimination and generalization is critical for avoiding danger without excessively forgoing exploration and reward-seeking (Dunsmoor and Paz, 2015). Preventing overgeneralization requires circuits that constrain fear responses (Reviewed by Korzus, 2015), and these circuits are not well characterized (Dymond et al., 2015).

Overgeneralization is associated with abnormal reactivity in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) (Greenberg et al., 2013), and patients with mPFC damage exhibit both abnormal behavioral inhibition and altered autonomic responses that perturb decision-making and learning about risk (Bechara et al., 1997; McKlveen et al., 2015). The Stujenske lab aims to develop an integrated understanding of parallel manifestations of fear states (behavioral and somatic) and link them to prefrontal cognitive microcircuits that discriminate between fear and safety. In doing so, we aim to clarify how fear states are bidirectionally regulated to support adaptive decision-making.

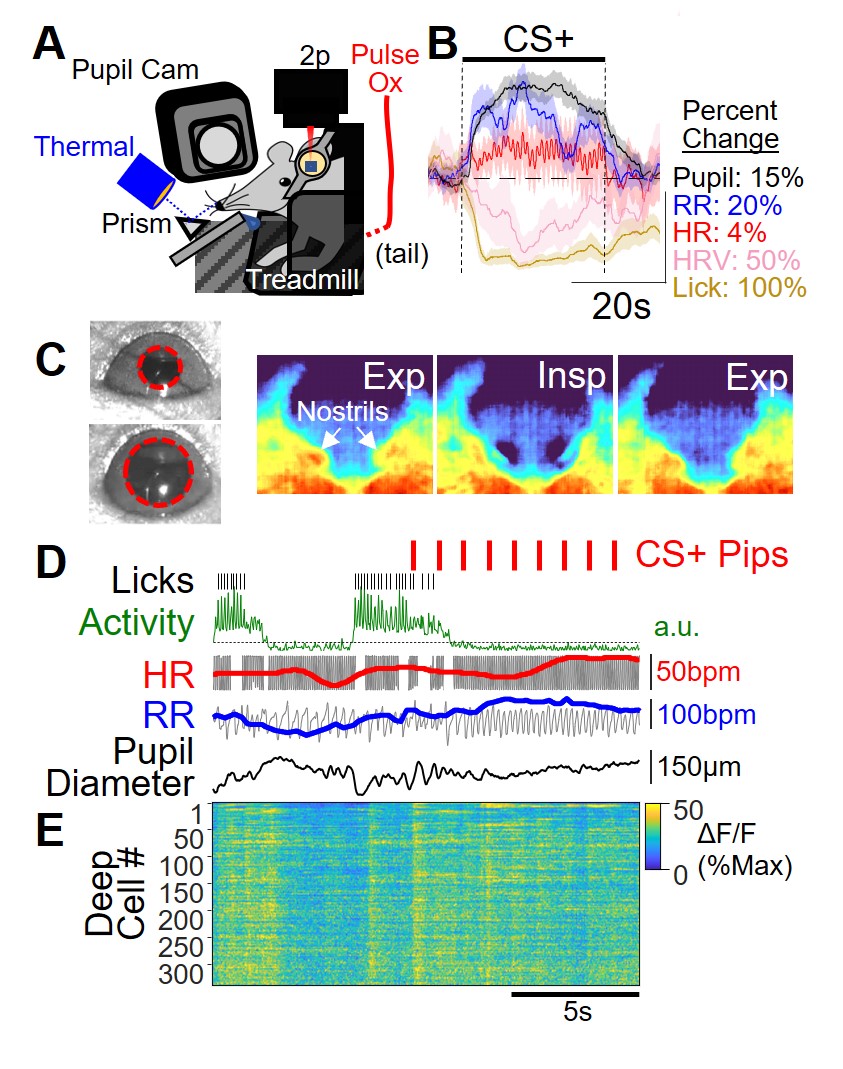

Our lab uses computational methods and multiple complementary system neuroscience techniques to pursue this goal. To investigate the relationship of defensive behavior and somatic response, Dr. Stujenske developed a way to non-invasively monitor behavior, respiration rate, heart rate, and pupil size in head-fixed mice (Fig 1A). Mice freely lick for water, but after differential fear conditioning, in which one tone is paired with a shock (CS+) and another tone is explicitly unpaired (CS-), the CS+ triggers mice to immobilize and stop licking (Fig 1B-D). Notably, this occurs with changes typically associated with sympathetic activation (Fig 1B). All of this is monitored while the activity of individual cells is tracked using two-photon calcium imaging.

Inhibitory control of the amygdala

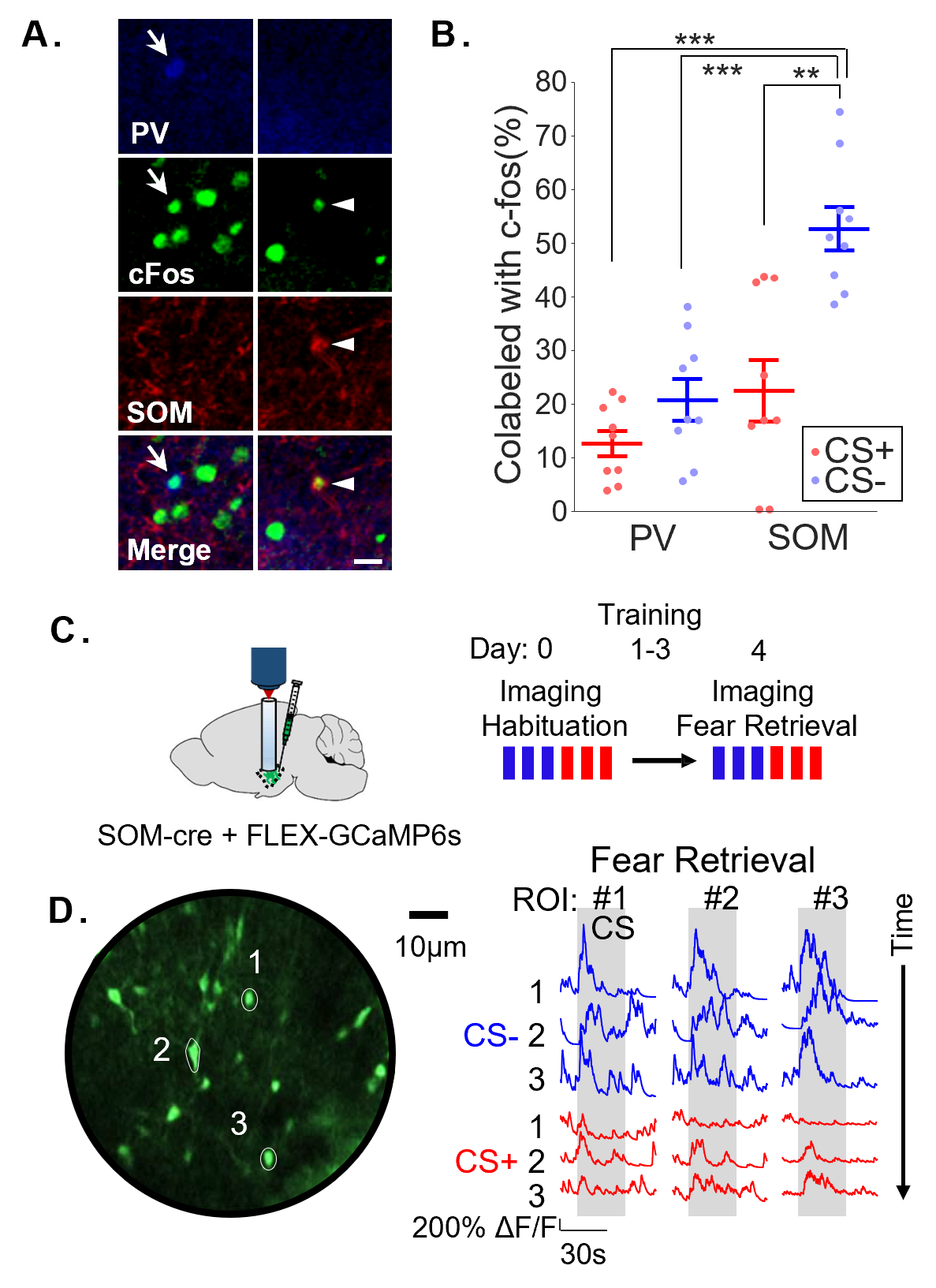

The lab is particularly interested in the role of cortical recruitment of inhibition in subcortical structures for affective regulation. In his postdoctoral work, Dr. Stujenske investigated the cell-specific consequences of prefrontal inputs to the BLA during fear discrimination. Using two-photon imaging, optogenetics, and in vivo electrophysiology with opto-tagging, he and his collaborators demonstrated that BLA somatostatin-positive interneurons (SOM IN) robustly and specifically respond to non-aversive cues, while parvalbumin-positive interneurons (PV IN) do not (Stujenske*, O’Neill* et al., 2022). During non-aversive cues, SOM IN actively block patterns of theta frequency activity associated with fear. Thus, silencing SOM IN, but not PV IN, worsened fear discrimination. SOM IN response to non-aversive cues was entirely dependent on the dorsal mPFC, and discrimination could be rescued in overgeneralizing animals by stimulating dorsal mPFC inputs in BLA.

This was a surprising dissociation from the process of extinction, in which repeated presentations of a conditioned cue leads to re-learning that the cue is not aversive. The findings are strikingly different from extinction in two ways: 1. In general, dorsal mPFC has been shown to either not affect or oppose extinction (Review by Giustino & Maren, 2015). 2. Disrupting BLA PV IN-mediated perisomatic and axo-axonic inhibition impairs contextual and cued fear extinction, respectively (Saha et al., 2017, Davis et al., 2017), but silencing PV IN did not affect discrimination. Future work in the lab will aim to understand differences in the inhibitory control of extinction and discrimination and how learning shapes interneuron activity during these processes.

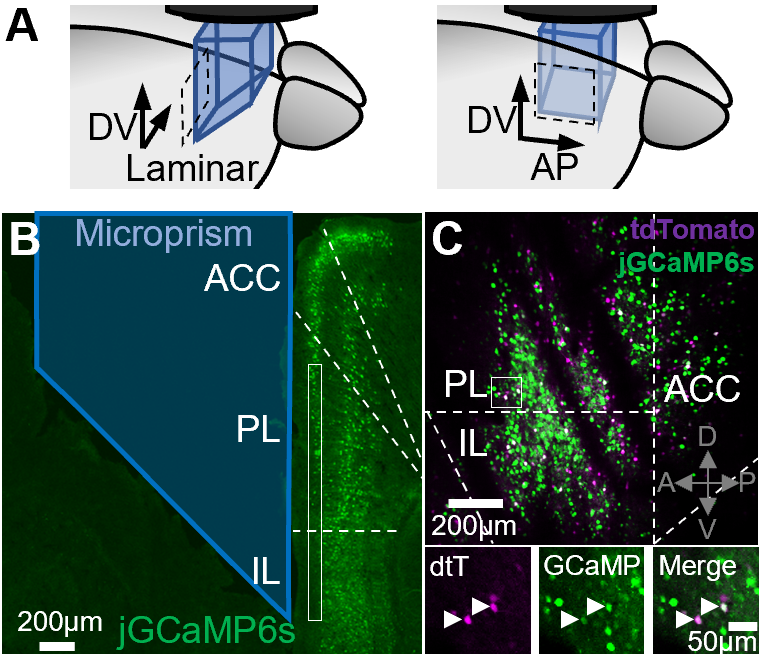

The spatial topography of medial prefrontal cortical encoding

The medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) has been primarily subdivided along its dorsal-ventral axis. In the mouse, the main dorsal and ventral mPFC regions are called the prelimbic cortex (PL) and infralimbic cortex (IL), respectively. Many groups have described differences in the function of these regions for regulating defensive behavior related to feared outcomes. The PL has been primarily implicated in the expression of defensive behavior after learning, while the IL is involved in the extinction of learned aversive associations, through repeated experiences of a feared stimuli without the anticipated threat occurring (Review by Giustino & Maren, 2015).

Dr. Stujenske’s novel finding that PL prevents overgeneralization of fear responses, via gating of dendritic input by BLA SOM IN (Stujenske*, O’Neill* et al., 2022), demonstrates a pathway for prefrontal cognitive control of fear. Given that PL also supports fear expression (Giustino and Maren, 2015), the findings suggest that PL bidirectionally regulates fear. In rodents, defensive behavior has been used as a proxy for internal fear state, but many somatic changes occur simultaneously. The mPFC is a critical region regulating both defensive behavior and autonomic reactivity during fear (McKlveen et al., 2015). How these prefrontal regulatory functions (behavioral and somatic) relate is unknown.

A key aim of the lab is to characterize the spatial topography of fear state encoding within the mPFC, not only again its dorsoventral axis, but also along its laminar (mediolateral) and anteroposterior axes. Preliminary data from the lab suggests that there are meaningful distinctions along these axes with regards to information encoding and regulation of fear response, both behaviorally and somatically.